|

| Main Menu - click above |

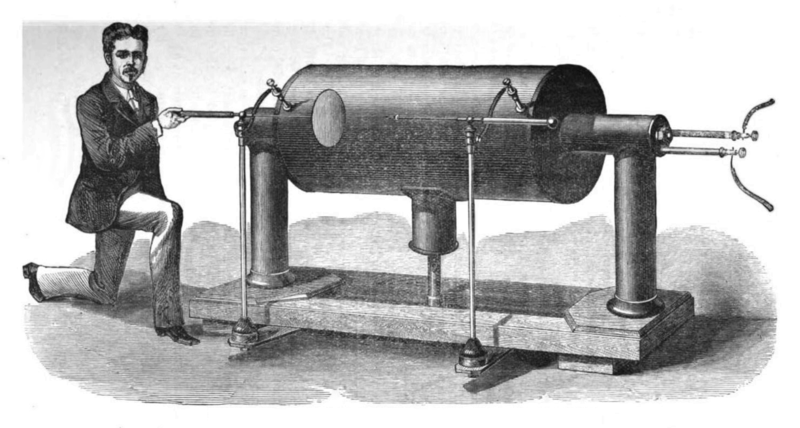

STEAM GUN OF 1824 |

Diagram & following description is from The London Mechanics` Register, 6th Nov 1824 --

A - The Chamber of the Gun, from which the Barrel is charged.

B - The Handle which directs the piece working in the Chamber, and by means of which the Balls are conveyed from the Hoppers (C) into the Barrel.

C - The Hoppers, into which the Balls are placed, and from which they drop one by one into the Chamber, when the Handle (B) is moved to its extent.

D - The Barrel, which is about six feet In length.

E - A Regulating screw, by means of which the Handle is kept tight.

F - A Swivel Joint, which allows of the Gun being elevated or lowered to any point, and by means of which the Barrel may be moved in almost any direction.

G - A Throttle Valve, by which the steam is admitted from the Generator of the Engine, and into which the Pipe, communicating with the Barrel, is introduced.

H - Mr. Perkins` admirable mode of uniting Pipes so as to resist any pressure. This represents the junction of the Pipe from the Generator with that from the Chamber.

The following description was written by W.H.B.Smith, as included in chapter 3 of his excellent book, Gas, Air & Spring Guns of the World, 1957.

The inventor, Jacob Perkins, is all but unknown in American history today - yet his genius contributed greatly to our present day comfort and to mechanical and even social developments.

He was born at Newburyport, Massachusetts, at the mouth of the Merrimac River, on July 9, 1766, His ancestors had landed at Ipswich in 1630. At the age of about 12 he was apprenticed to a goldsmith. His master died 3 years later, and young Perkins continued to operate the business! While still only 15 he invented a process for plating shoe buckles-a good business in that day-and the business prospered. He was so remarkable a craftsman that when he was barely 21, the State of Massachusetts commissioned him to make the dies for the State's copper coins! At the age of 31 he invented a machine for heading and pointing nails and tacks in a single operation, a most remarkable invention in its day; but he fell in with promoters who ruined him, while others profited from the invention.

He moved to New York and later to Philadelphia where he developed probably the first steel plates for banknote engraving, a system of preventing banknote forgery which was widely acclaimed and used, methods for hardening and annealing steel, and a wide variety of other items.

Unable despite his ability and energy to get proper financial backing here, he moved to England in 1818 taking a group of his craftsmen with him. America's loss was Britain's gain. In England he received financial support. He started a successful banknote business and went on to develop instruments for measuring ships' speeds, for determining diving depths, and a score of other devices.

When he turned his attention to steam development, this amazing man really hit his stride. He developed a single-cylinder steam engine with a boiler capable of holding the then unbelievable pressure of 800 pounds.

When pistons didn't stand up, Perkins produced a special alloy which gave a machined finish requiring no lubricant, together with all the other required physical properties. Then he produced his steam gun.

The Duke of Wellington became very interested in this Perkins gun, but even with this support Perkins had two strikes against him in trying to deal with the professional military minds. First, he was a "Colonial" not far removed from Concord, Lexington, and the year 1776. Second, he was trying to convince a professional military body, a group which in any age has been, is, and probably always will be slow to accept the new. Like Texas Judge Roy Bean's approach of "Let's give him a fair trial and then hang him!" the military bodies approached the Perkins gun convinced it just wouldn't work anyway! Due to Wellington's interest they at least had to listen.

In the first trials before the Iron Duke and his engineering officers, Perkins streamed volumes of lead musket balls against a 1/4-inch iron plate to demonstrate close quarters accuracy and destructive force. His steam pressure was now up to some 900 pounds, low by comparison with any gunpowder even of that day, but unbelievably higher than had ever before been achieved; and sufficient to completely shatter the projectiles against the iron target.

When the penetrating power was still questioned, Perkins fired at a set of eleven 1-inch planks spaced for testing. All 11 were penetrated. Tough iron projectiles punched through a 1/4-inch iron plate! All the penetration tests were at 35 yards from the muzzle, then a good musket distance. If we remember that a penetration of 1/4-inch in pine is considered equal to a dangerous human wound, the significance of the tests stands out; particularly in that day of muzzle-loading, singleshot weapons.

Perkins then screwed a tube to the gun barrel which would feed the balls in by gravity to make a sort of machinegun. This device worked. The next step was a wheel mounting carrying several such tubes, spoke fashion, which could he brought into play for rapid fire. The fantastic firing rate of 1,000 shots per minute was thereby obtained-all this remember in the year 1824!

By attaching a movable joint to the barrel, Perkins sent bullets down a 12-foot plank, spacing them to show that a military company charging in the approved fashion of the time would have had every soldier in the line down with a bullet in the brisket! Another attachment allowed shooting around corners-a device introduced by the Germans for block-fighting in streets and for getting at blind corners from inside tanks during World War II!

Some of the military objections raised were really interesting; as for example, the steam pressure would deform the musket halls in firing them! Accuracy penetration, rate of fire-those were not questioned. But deforming the projectiles was a very serious consideration!

The French became interested, and at Greenwich Perkins conducted exhibitions for Prince Polignac and a group of French military engineers. They specified a design to fire sixty 4-pound balls a minute. Perkins agreed to adapt the gun. Then they wanted it to shoot musket balls, machinegun style also. Perkins obliged. When it came to spending money to buy the guns, however, all dragged heels, and nothing eventuated.

The Greeks wanted a couple to chase the Turks out of Patras-an old story still new. "The Russian Autocrat," as one writer of the day put it, "has been vainly negotiating for a park of them." That word "vainly" stands out. Perkins was a man of principle as well as ability.

Meanwhile cartridge development was moving ahead -thanks to civilian sporting development for the most part. Percussion caps had come into being and the era of the "fixed" cartridge was in sight. These developments, together with the practical difficulties of working with steam under high pressure in the field, canceled out any acceptance of the steam gun. True, cannon were still muzzle-loading, and the French now toyed with the idea of Perkins steam cannon on warships because of rapid fire, close-quarters, and boarding value; but warfare too was changing rapidly.

So Perkins patent 4592, British, of May 15, 1824 came to naught as a gun; but from its development the inventor and industry learned much about handling high-pressure steam which was incorporated into home and industry usage. We have no space here to pursue those collateral developments, however.

Opinions on steam guns, warfare, and Russia as expressed by the learned editors of The London Mechanics` Register, November 1824.

"If Mr. Perkins's steam guns were introduced into general use, there would be but very short wars; since no fecundity could provide population for its attacks. . . .

What plague, what pestilence would exceed, in its effects, those of the steam gun? - 500 balls fired every minute . . . one out of 20 to reach its mark - why, 10 such guns would destroy 150,000 daily. If we did not feel that this mode of warfare would end in producing peace, we should be far from recommending it. . . .

We have heard, but we do not vouch for the fact, that the Emperor of Russia, who has more knowledge of the importance of steam than some of us Englishmen, has sent an agent to procure a supply of Perkins's steam guns, which that gentleman's patriotism will not allow him to offer. . . ."

|

| Please help beat cancer - DONATE click above |

Unrelated to this post, below is an example of

eclectic science esoterica

A large induction coil made in 1877 by British instrument maker Alfred Apps for British scientist William Spottiswoode. One of the largest induction coils ever constructed, it could produce a spark 42 inches (106 cm) long, corresponding to a voltage of roughly 1,200,000 volts.

It was 44 in. in length, 20 in. in diameter, mounted on 3 insulating wood posts. This drawing shows the coil only; the interrupter, capacitor and liquid batteries needed to generate the primary current are not shown. Its primary winding, seen extending from the ends of the secondary coil, consisted of 1344 turns of .096 in. copper wire wound on a 3.56 in. core made of parallel iron wires. There were actually two primary windings, which could be exchanged; the other was for higher current work. The secondary consisted of 280 miles of wire wound in 341,850 turns. Powered with 5 quart-sized liquid Grove cells, it gave a spark of 28 in., with 10 cells 35 in. and with 30 cells 42 in. Information from William Spottiswoode, The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 15, Jan 1877, p. 30.

|

| Main Menu - click above |